Taking Up Serpents

And these signs will follow those who believe: In My name they will cast out demons; they will speak with new tongues; they will take up serpents; and if they drink anything deadly, it will by no means hurt them; they will lay hands on the sick, and they will recover. Mark 16: 17-18.

There’s a curious thing that happens if you spend enough time pursuing a particular hobby. The Great Regression. For seemingly no reason at all, you may find yourself deprived of all those years of practice. Every chord on a guitar foreign. Every stitch on a piece of leather crooked. Or, as is most common for me, every step of a run feeling like a wobbly-legged foal in clover. Call it overuse or stress accumulation, but for two weeks I’ve been running as if I never have before. Aches in every joint. Heartrate sky high. At first, I blamed the heat. Here, in southern Ohio, summer can be a mixed bag. The lucky draw this year is intense heat and suffocating humidity. But the truth of it is, fault often falls at my feet, those two heavy bricks which no longer want to turn over.

As I’m driving home, considering never running again, I spot it——a rattlesnake dead-centered on the gravel road. I slow the car down and pull directly beside it, blocking the crossing it was attempting to make. A divine yellow morph that has recently shed, stretching three, three-and-a-half feet, toward me. The snake, being practically blind, moves its head back about an inch and freezes. It never even rattles. Kinz wants to move it so some boozer in a truck doesn’t hit it for sport. This is, unfortunately, quite common on our remote backroads. But I don’t feel like messing with a snake simply trying to cross the road. Not on legs I’ve lost my faith in anyway.

Despite having experienced sixty to seventy rattlesnake sightings, most of those within twenty feet of my front door, this is my first sighting on Road Two. There is, for those who’ve never experienced it, a palpable electricity that pumps through you in the presence of a timber rattlesnake——that last great symbol of undiluted wildness.

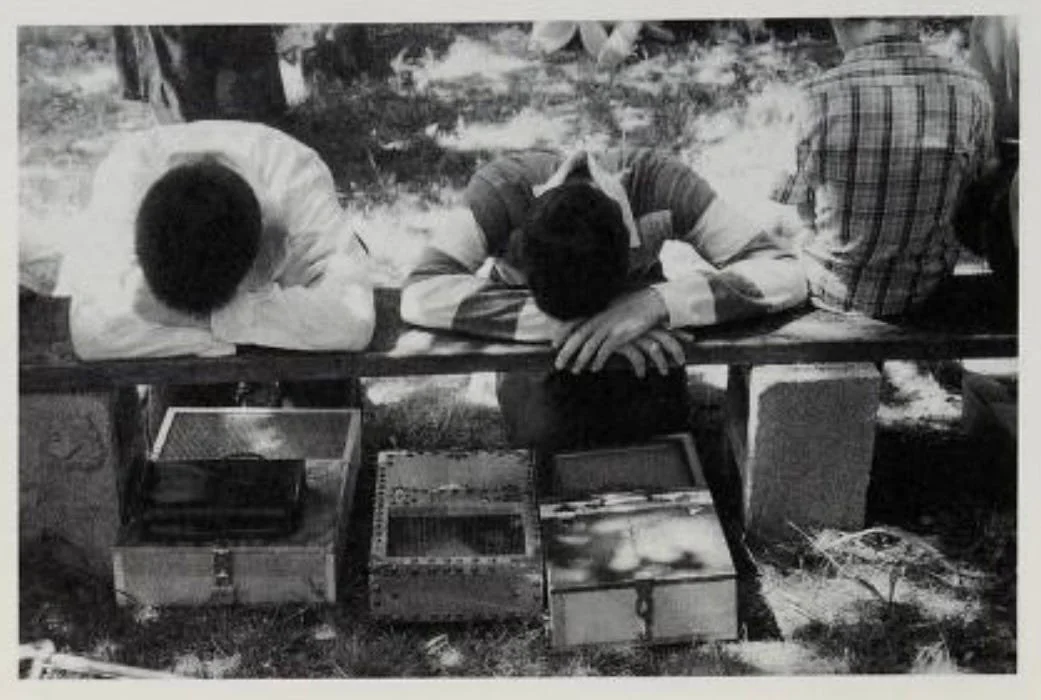

Praying at a Saylor Cemetery Homecoming - Snake boxes under the bench - 1990.

Over the years, I’ve fallen down the rabbit hole, or perhaps slithered into the den, of obsession and curiosity over these snakes. It began as research for a story I was writing, which lead to a documentary from 1977, The Jolo Serpent Handlers, an in-depth profile on the Pentecostal snake-handling church of Jolo, West Virginia. After the initial shock wore off, I was compelled by those enraptured services caught on camera. Lots of shaking and shouting and sweating, stimulated by music that can only be described as acid-soaked rockabilly, and not to mention the rattlesnakes draped across necks and hands like some deadly fashion accessory. Drinking poison, often strychnine or carbolic acid, was just the icing on a very odd cake.

The origin of this practice inside the United States is often accredited, whether accurately or not, to the Pentecostal pastor George Hensley. In 1910, after witnessing a man hold a venomous snake without being bitten during an outside church service in Tennessee, young Hensley felt a kind of calling. Obtaining eternal life after death, he figured, required risking life while on Earth. He climbed White Oak Mountain, stopping at a place known as Rainbow Rock, and found a large rattlesnake basking in spangles of sunlight. Story goes, it was at this moment God bestowed upon him a special ability. A kind of prophetic suit of armor. He took up the rattlesnake, held it toward the heavens, and cemented his legacy as the Saint of Serpents.

George Hensley preaching near the Hamilton County Court House in Chattanooga,Tennessee - 1947

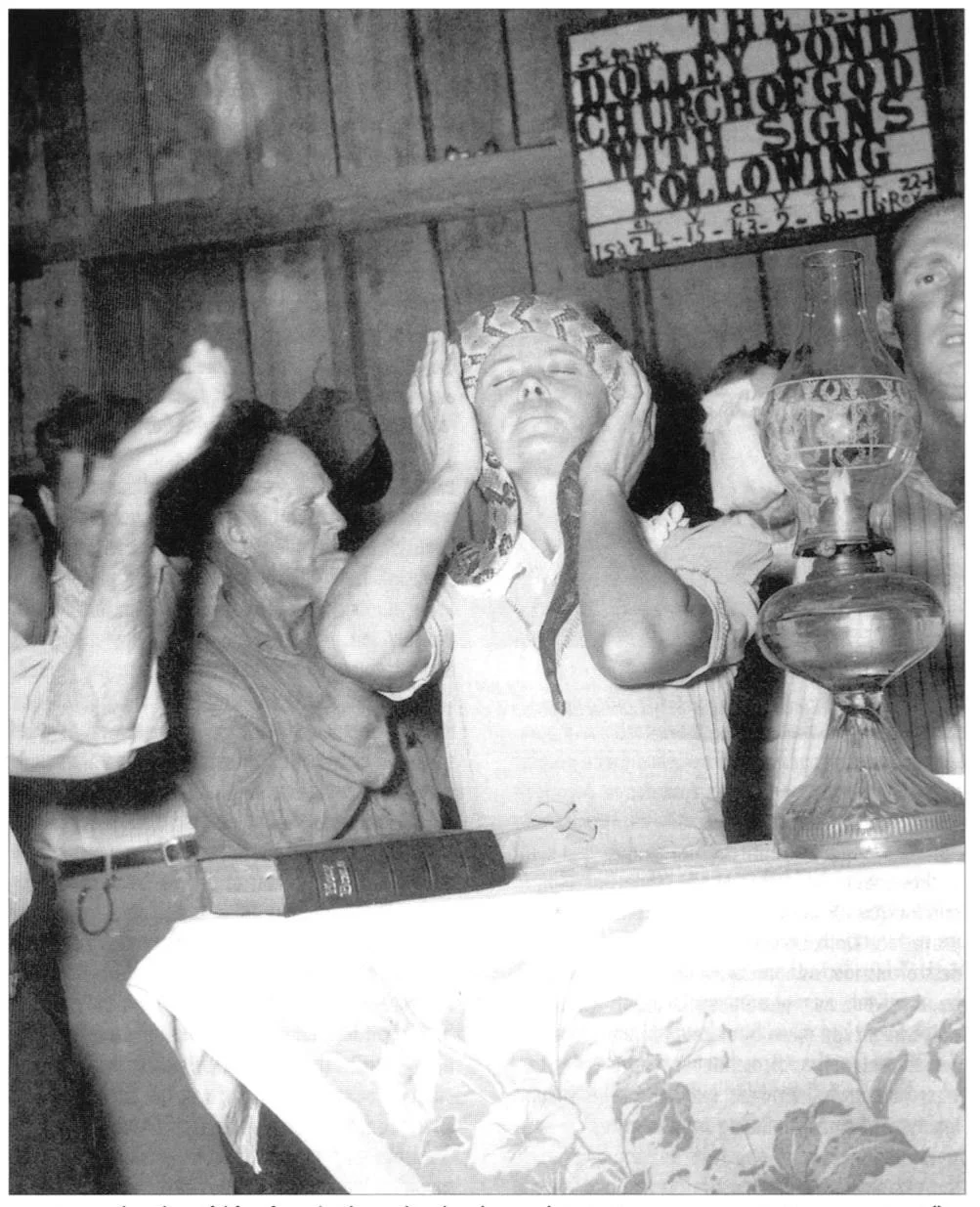

Hensley established the Dolley Pond Church of God with Signs Following near Birchwood, Tennessee. As you might imagine, people were compelled to travel and hear this very peculiar gospel. By blending supernatural signs from the Holiness movement with the ecstatic and emotional worship from the Pentecostal movement, the practice of snake handling began to grow throughout rural Appalachia. Belief was, bitten or not, the outcome was God’s will.

Lewis Ford and Minnie Parker. Ford died shortly after this photo was taken - 1945

Minnie Parker with rattlesnake - 1947

At its peak, during the early to mid-20th century, there were several thousand adherences. A keen-eyed observer would notice these were often socially isolated communities which forged a sense of identity in the biblical literalism of an uncompromised faith. However, Hensley’s armor would appear to have some limitation. He died on July 25th, 1955, after suffering a rattlesnake bite during a service. Hensley, like others who would die in the following generations, refused medical care, believing his faith alone would heal him. His wife reported his last words as, “I know I’m going. It is God’s will.” His death, however, was ruled a suicide.

My interest in these snake handlers spiraled. I even considered making a pilgrimage of sorts to Jolo, West Virginia, capturing my own photos and documenting, in writing, the remnants of what those folks built. But it was only after I read Dennis Covington’s Salvation on Sand Mountain that I began to see the light. Covington was sent to Scottsboro, Alabama to cover the trial of Reverend Glenn Summerford, who was convicted and sentenced to ninety-nine years in prison for attempting to murder of his wife with rattlesnakes. Quite unexpectedly, Covington realized the trial was a mere catalyst for his own spiritual quest. Over the following years, he attended several snake-handling services at different churches along the southern Appalachian region, peeling back the harden layers of stereotype associated with these poverty-plagued locations. He became friends with many of these members. What was apparent while reading the book was the genuine sense of community that tied these people together. Everyone was welcomed, even a journalist writing an invasive story. Covington took up a serpent or two and even preached a sermon before heading down a path that led away from the church. But that book made me realize I didn’t need to comprehend the why, but I could at least appreciate the sense of conviction in which they acted.

Timber Rattlesnake on Road Two

In the rearview mirror, the rattlesnake on Road Two becomes a faint line behind the cloud of dust kicking up from the tires. The AC struggles against the oppressive heat pushing through the windows. July’s undergrowth along the side of the road is already thinning toward August. Buzzing still, I can’t even remember what was bothering me before I stopped the car. Having metaphorically taken up a serpent, I feel only the overwhelming sense of renewal. And that I can understand.

“Listen up. The peculiarity of Southern experience didn’t end when the boll weevil ate up the cotton crop. We didn’t cease to be a separate country when Burger King came to Meridian. We’re as peculiar a people now as we ever were, and the fact that our culture is under assault has forced us to become even more peculiar than we were before. Snake handling, for instance, didn’t originate back in the hills somewhere. It started when people came down from the hills to discover they were surrounded by a hostile and spiritually dead culture. All along their border with the modern world — in places like Newport, Tennessee, and Sand Mountain, Alabama — they recoiled. They threw up defenses. When their own resources failed, they called down the Holy Ghost. They put their hands through fire. They drank poison. They took up serpents.” - Dennis Covington, Salvation on Sand Mountain